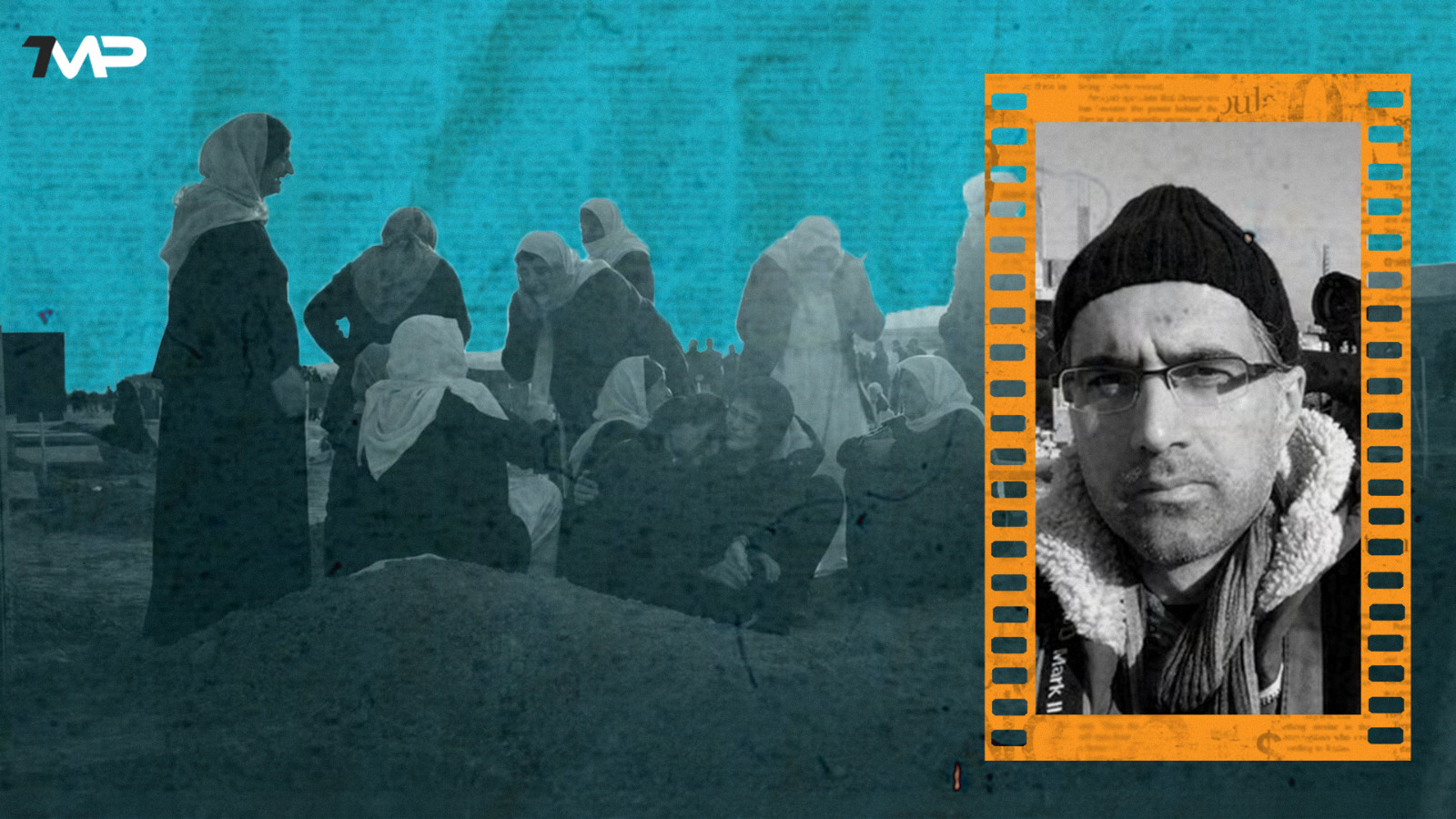

Interview with filmmaker Reber Dosky on ‘Daughters of the Sun’: “We have abandoned the Yazidi people”

In August 2014, the province of Sinjar in southern Kurdistan, which is mostly inhabited by Yazidi people, was attacked by ISIS. The invasion, in which thousands of Yezidi men were executed and thousands of women and girls were kidnapped and sold as sex slaves, went down in history as the Sinjar genocide. Many women who survived the enslavement of ISIS are still striving to heal the wounds caused by the genocide.

Reber Dosky, a Kurdish film producer residing in the Netherlands, shot ‘Daughters of the Sun’, a documentary about the recovery process of Yazidi women who survived the captivity of ISIS. The world premiere of the documentary, which depicts how a group of Yazidi women and girls who came together in a refugee camp, to build their future with the support of Hussein, a wise theater actor, will take place in The Hague on March 25. The documentary is nominated for the Dutch Movies That Matter award.

‘Daughters of the Sun’ is not Reber Dosky’s first nominated work. Two nominated documentaries of the filmmaker have won awards; He received the IDFA Award for best documentary both for ‘Radio Kobani’ in 2016 and for ‘Sidik and the Panther’ in 2019. Award-winning director Reber Dosky answered our questions about his documentary.

Why did you decide to make a documentary about Yazidi women?

ISIS militants carried out a large-scale attack against the Yazidi community in Sinjar. Several elderly men and women were slaughtered. They kidnapped children and young girls and used them as sex slaves. In 2015 I got to meet one of those girls. She escaped from the hands of ISIS on her own. Her story led to the short film “Yazidi Girls” which was released in 2016.

The story of the three girls in ‘Yazidi Girls’ and their thousands of fellow sufferers has always stayed with me. I immediately wanted to make a feature-length film about it, but it was too early for that. They needed to calm down first to smooth the rawest edges of their trauma. All the while I kept in touch with more liberated young women and children. We worked together to build their trust.

Can you describe that process?

I think it’s special that these women have allowed me into their lives and that they have had faith in this project. They all lost faith in their fellow human beings, which is quite understandable after all that has happened to them. ISIS tried to dehumanize the Yazidi people, especially the women, but they did not succeed. For me, this film is dissimilar to my previous work. I was aware of the fact that these women had gone through extraordinary things, that the pain and the grief were very deep.

How were the characters in the documentary involved in your project?

Through various contacts I got acquainted with Hussein, a theater maker. He volunteers for the liberated women. He is a kind of bridge between society and women. I met the characters in the film through him. For a long time I focused on building trust and didn’t ask them any questions. I explained how I wanted to shape the documentary and what my style of filmmaking is. They were cautious because of experiences with journalists who wanted to get under their skin for a report. I made it clear that the filming process will take three years and that my approach will be different. We started doing fun things together. At that time I also worked with Hussein, who is blindly trusted by the women. It helped a lot that I got in touch with them through Hussein. At the end of the recording, Sarap said: “We were all careful with your crew, because you were all men, but now I’m very sad that it’s over.”

What was it like working with women who had experienced such deep trauma?

It wasn’t easy as their wounds were made by men. At first they were distant, but I didn’t force anything. We had to give the characters as much time as it takes to get used to us. That was also a reason why I started to shoot the documentary after a few years. Some women were already processing their trauma. They already had insight into their lives and what had happened to them. Others were still too deep into it to be able to narrate properly.

Several countries and international organizations have recognized the Yazidi genocide. What are your thoughts on this development?

Since it is crucial for the Yazidi people that their agony is recognized, I believe it’s essential that all countries recognize the genocide. It also provides strong grounds to prosecute the perpetrators. The Genocide Convention states that perpetrators must be punished by their own country or by an international tribunal. It’s hard for the survivors to feel justice when the perpetrators are still on the loose.

What about your notion on the current stance of the international community towards Yazidi people?

We are going through tough times where many things happen rapidly, so it’s hard to focus on just one issue. The genocide of the Yazidi people was committed in 2014. Who is still talking about that in 2023? Nowadays, Ukraine is the center of attention, which is understandable, because the war there has more impact on our daily life. However, I think that we have all abandoned the Yazidi people. At the moment, 3000 Yazidi children, women and men are still missing. ISIS members, who fled from Syria to Turkey, have forcibly taken many Yazidi children and women with them. Unfortunately, there is no way to cooperate with the Turkish government on this matter. And in European countries we don’t hear anything about it anymore. Regardless of what we think, the only thing that occurs in the Netherlands is the repatriation of ISIS women and their children, but I believe that the Yazidi community also merits our concern and assistance.